Is it an early Georgian flitch

beam? Or a shallow truss?

This week we will look at an

interesting structural beam I found a little while ago. I was called to a

mansion house in Kent, the building is Grade 1 Listed due to its very fine Georgian

plasterwork to its ceilings on the ground floor. While the building is mostly

Georgian, in the 1950’s it was extensively re-worked, the plasterwork was left

untouched and remains preserved within the building.

The client called us in because

the plain ceiling and cornice were cracking in several of the main rooms on the

ground floor.

The two ceilings which were being

looked at were the original ornately decorated 1735 ceilings and are the most

important historical part of the building’s interior. Therefore great care was

required in any proposed repair. Before any physical interventions were to take

place we needed to understand the situation in much more detail, this

understanding took place as follows:

- Historical research

- Environmental assessment

- Structural investigation

- Plaster investigation and assessment

- Consultation

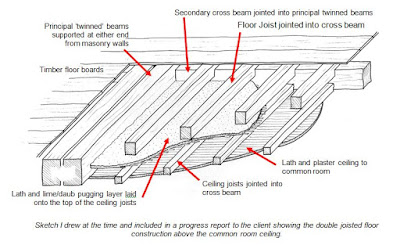

The structural of the ceiling and

floor above the second main room was found to be a double joisted floor, while

it had an interesting ‘daub’ layer, possibly for sound insulation. There was

nothing unusual in this floor type in a house of this age and grandeur. This

floor structure had two principle timber beams, from which the whole floor was

supported, it could be seen that these had deflected by 60-70mm at the centre.

The principal timber beams appeared

to be in two halves bolted together with a central element which was raised at

the mid point of the beam and was at low level at the ends with it ending

before the beams entered the wall, leaving the two beams separated by an inch.

This was observed in the floor above the main room, however the top of the

principal beam of the hall was visible and this gap between the two beams could

be seen.

The deflection in the principal beam had been

identified as a reason for the large crack across the secondary rooms ceiling,

however there was documentary evidence that this was the same in 2005,

therefore the movement was not fast. It was agreed by all that this principal

timber could be moving, however without long-term monitoring this would not be

known. With the engineer’s agreement I investigated the construction of the

principal beams, as these were similar to the principal beams in the main hall.

What I found was an oak timber which may have been under some tension. It was

held in a shaped recess between the outer timbers. The engineer had come across

this type of beam only once before, in that case the central element was an

iron shallow truss. It was thought to be a Georgian idea of increasing the

strength of a timber beam, however it seems to have had a weakening effect as

it required the removal of a lot of the timber from the outer beams.

The worst area of cracking in the hall was on

the beam which had a larger amount of deflection, horizontally along the plaster encasing the

principal beam. This was first thought to be due to structural movement,

however when the plaster conservator drilled several holes in this area no sign

of structural failure could be found behind the plaster. Some areas of the beam

were found to be laid to laths which had been fixed directly to the beams,

resulting in the plaster being applied without the space for any nibs to form,

this was resulting in the deflection of the beam to cause the ceiling to

continue to crack.

Therefore once the plaster repairs

were carried out it was agreed that we would place survey reflective markers

throughout the ceilings at strategic points and a survey firm be employed to

carry out periodical surveying, once a month for 18 months to ensure a full

season is recorded. A visual inspection over this 18 month period would also be

able to highlight any opening up of the repaired ceiling in the areas where the

worst cracks opened up. This monitoring will provide confirmation of any

movement during the course of the year. I will then monitor this and make

further decisions with the conservation engineer once this data is gathered.

The investigation work undertaken

on the principal beams provided information on the structural composition of

the floor. The long term monitoring will be an on-going item over the next

18-24 months. It will be interesting to see what this monitoring shows, if

there is movement then maybe some intervention will be required, however this

will be only if the movement is beyond the tolerance deemed to be acceptable by

the conservation engineer.

Comments

Post a Comment